Almost everyone is familiar with the famous Edison quote: “Genius is 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration”. To know much about Edison’s life, is to know that was certainly true for him – and many other creative individuals when you take the time to learn how they worked. Yet, there is still a strong sense among many that great ideas come to the gifted in the way lightning strikes, unpredicted and unexpected.

Insights as Idea Sources

In my experience, great ideas more likely come from great insight. The insight may also seem to come suddenly, but it almost always is preceded by solid spade work involving observation, experimentation, thoughtful reflection and search fueled by curiosity and almost relentless questioning. The analyst who repeatedly asks the question “why?” is most likely to be rewarded with insight.

It is through answering the why’s that we set foot on the trail to insight. Insight is penetration, a view of the inner nature of things. That view may reveal pattern – recognition that when certain conditions are present, particular events almost surely follow. At other times, an insight may be more about mechanism, establishing how a cause or chain of causes generates a certain effect. Sometimes it takes the form of a structure or a model that shows how phenomena relate to each other. It can also be about process – the steps that lead one set of conditions to change to another.

As complex and mysterious as it is, getting an insight is not anywhere near enough when it comes to planning or designing systems. Complex systems consist of many designed elements and relationships, all of which can benefit from insight. Understanding a system’s potential users alone can provide a wealth of good insights easily able to shape innovative new directions. The problem is capturing them and making sure they get into the planning process. How insights are transferred from the aha! event to a usable form of information is an important part of the answer.

Some time when you have an opportunity, ask about the research conducted for a project. Nine times out of ten you will get some variant of this answer: “right over here”, and a hand pointing to a filing cabinet. In the filing cabinet will be reports, publications, ethnographic video tapes, copies of articles from journals, photographs, web screen-dumps, downloads and a wealth of other archived remnants of what was probably an extensive fact-gathering research activity. The problem is, this is data – undistilled – in its original form. It may have had great value in shaping the search, informing the planning team and even revealing insight, but in its original form, it does not enter the information stream in a way suitable to have impact in the several places it should. Worse, if it is considered at all, important details are likely to be forgotten, even mis-remembered.

Data is not information. Information acquires its value through distillation, interpretation and the revelation of insight. At its best, information has surprise, and one measure of its value is how much. A crucial step in the analysis phase of planning is the recognition of insight and the thoughtful communication of it in a form usable in the information flow.

An Insight Document: The Design Factor

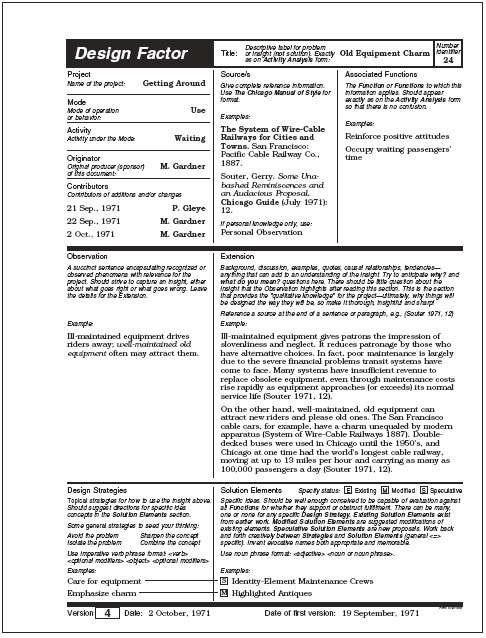

In Structured Planning, insights are thought through on one-page documents called Design Factors (see the Figure). As in other phases of the process, standardization is deliberately applied to the way in which information is presented, so that it can be readily contributed and used by anyone working with the planning process. A Design Factor document actually contains more information than just an insight, but we will get to that shortly. From the insight standpoint, the information is distilled into an Observation and its Extension.

Observations are succinct, usually one-sentence statements expressing the essence of the insight. In “Covering User Needs”, I introduced the idea of Observations as qualitative information elements and the evolution of their form through experiments with different formats seeking greater information content and more natural grammar. A form we use frequently introduces a condition and then completes a pattern by noting the effect that the condition typically produces. For example: “While moving through open spaces, crew members may inadvertently contact equipment with their feet.” This was a surprise to the designers of Space Lab; switches were being turned on and off unintentionally! We picked up this insight from their reports and used it in work we did for NASA on Space Station.

The form of the Observation isn’t rigidly constrained to the condition/effect format, however. As long as there is insight, the statement has value. An example of another form is the Observation from the Design Factor in the Figure: “Ill-maintained equipment drives riders away; well-maintained old equipment often may attract them.” This had direct bearing on concepts that we developed for Chicago’s CTA transit system.

The Extension section of the Design Factor is used to carry on the discussion. Experience has shown that considerable value derives from distilling an insight to a single sentence. Through this process, what is important and not so important gets sorted out. But communication may also suffer from the distillation, and we found ourselves far too often asking “why” and “what do you mean by that” questions of Design Factor originators. The result was the Extension section, where these kinds of questions can be answered, and the insight augmented with additional information on causes, effects, relationships, contexts, associations, etc. that help to explain why the phenomenon exists.

Combining Insight and Ideas

The Design Factor document, as earlier suggested, also contains other useful information. Contrary to the design model that suggests that the path of development progresses neatly from analysis to synthesis to evaluation in discrete steps, Structured Planning is much less firmly partitioned. During the information gathering activity, when understanding and insight are being sought, the analyst is expected to think about solutions in the midst of finding problems – and to apply some practical screening at the same time as a preliminary form of evaluation. Thus, the Design Factor document in one place contains ideas as well as insight. The document’s design takes inspiration from the fact that when an insight about a problem is gained, it is often easiest then to see solutions for it.

The bottom half of the Design Factor form is devoted to ideas. On the left, the view is strategic. In the document in the Figure, two strategies are given for using the insight that well-maintained old equipment can have charm: (1) care for old equipment, and (2) emphasize its charm. On the right, ideas for specific implementation of the strategies are given names as titles for “solution elements” – potential component concepts for a system solution: Identity-Element Maintenance Crews (teams that would be assigned to specific equipment to maintain as their own), and Highlighted Antiques (older devices, equipment and environments spotlighted with placement, lighting, painting and other attention-awarding means). The titles are place-holders for more detailed discussions and explanations documented separately. In my next article I will talk more about this and how best to capture ideas quickly and efficiently when they occur.

Insight is the motive force. In advanced planning for system concepts, hundreds of insights are needed. The reward is true innovation across the system. Making the effort to distill data to information and to standardize its communication has a big payoff. And the payoff continues beyond the project. Companies and institutions across the country lose highly valuable information every day as employees retire, change jobs and otherwise move within the organization or leave it. The data stay – the memos, plans, reports, drawings – but the reasons why things were done the way they were, disappear. The qualitative information – the why’s, the insights – go. Probably billions of dollars worth of information are lost every year because there is no qualitative knowledge base to match the quantitative systems that most companies and institutions possess.

Design Factors are elements of that kind of knowledge base.