The most profound innovation since the assembly line is staring us right in the face. But we don’t see it because we are so busy looking for something else. For most of us the word “innovation” still conjures up images of amazing new gadgets such as technology to turn water into gasoline, black boxes to project moving 3D holograms from our TV sets, and bio-tech breakthroughs that reverse the aging process. Of course, some of these things will come to pass. But in our fixation on individual gadgets we are missing an innovation that is based on process more than it is on technology. A hundred years ago there was a similar process-based innovation in business that was so profound it became the basis for the economy of the industrial age. That process was the assembly line.

The assembly line and industrial technology are so intertwined in most people’s minds that they do not realize industrial technology had been in widespread use for 50 or 60 years before the assembly line was introduced. It was the process innovation called the assembly line and not new technology that brought our current consumer economy into existence.

The next wave of innovation and productivity will again be based on process and not new technology. A combination of processes that are coming to be collectively known as the “real-time enterprise” will become the basis for our economy in the information age. The real-time enterprise is an organization that employs a set of processes enabled by existing information technology and an organizational structure that allows it to acquire and act on up-to-date information to continually improve existing operations and devise new operations as opportunities arise.

Markets are constantly moving. Product life cycles are measured in months or a few years, no longer in decades. Companies cannot fine-tune their operations to fit some present set of conditions and then expect to simply run those operations unchanged for years and years. That was the old industrial model and that model no longer yields the profits we seek. We need something much more responsive––something that constantly adjusts to changes and opportunities.

The effect of a thousand small adjustments in the operating processes of a company as its markets change is analogous to the effect of compound interest. A real-time organization constantly makes many small adjustments to better respond to its changing environment and in doing so it steadily reduces costs and increases revenues. No one adjustment by itself may be all that significant, but the cumulative effect over time is enormous.

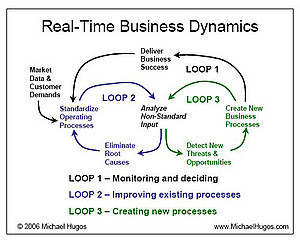

Traditional organizations are now caught in an inexorable squeeze as profit margins on their commodity products and services are relentlessly ratcheted down by the global economy. Soon those companies that cannot earn profits from constant small adjustments will hardly be profitable at all.There are three essential processes that combine to bring the real-time enterprise to life. Those processes are illustrated in the exhibit below. The three processes are activity loops enabled by information technology that occur continuously and simultaneously. The first loop (Loop 1) is for monitoring the environment and deciding what needs to be done. This is the process that is responsible for making the decisions that deliver success. People in this process are the ones that decide what a company should do.

Once a decision has been made, one or both of the other two loops are engaged to act on the decision. People in these processes are the ones who decide how something will be done. One loop (Loop 2) is for improving existing operations–that is what delivers efficiency. The other loop (Loop 3) is for creating new operations—that is what delivers effectiveness. Through the combination of these three loops an organization can sense and respond to change in a way that is both efficient and effective.

These three loops describe how work is organized in a real-time enterprise. The other key concept in a real-time enterprise is how work is carried out.

Work is carried out by a network of largely autonomous operating units. Each operating unit has the resources and authority it needs to do its job.

There is a central coordinating body that sets overall enterprise performance goals but it is up to the operating units to figure out how they will act and achieve their goals. Real-time enterprises push decision-making and authority out to autonomous operating units because that is the only way to be fast enough and responsive enough to consistently capitalize on opportunities and respond to threats as they arise.

Lest this seem like just an interesting theoretical discussion, consider the example of two very successful organizations that adhere closely to these operating and organizational principles. Both of these organizations have arrived at similar operating models despite being in very different lines of work and coming from quite different directions. The first organization is the United States Marine Corps. The second organization is Whole Foods Market.

The Marine Corps is perhaps the epitome of an effective modern, mobile military organization. Whole Foods Market is a $4.5 billion grocery chain that is outperforming all of its competitors (including Wal-Mart) and is setting new levels of profitability with operating margins that are nearly twice that of other large grocery chains. Both of these organizations represent striking examples of how the application of real-time operating principles can deliver a whole new level of performance and results.

Both organizations are composed of highly autonomous operating units. The basic operating unit of Whole Foods is not the regional office or even the individual stores but the store team. Every store is composed of eight or more teams–the produce team, the bakery team, the checkout team, etc. These teams roll up into stores and regions but performance is always evaluated and rewarded at the team level. The basic operating unit of the Marines is the platoon, not the regiment or division. Platoons of infantry, armor, artillery, etc. are combined as needed to create expeditionary units or task forces appropriate to the mission assigned to them.

Both of these organizations employ a highly decentralized organizational structure and decision-making process. Basic strategic doctrine of the Marine Corps is put forth in a short, 110-page book titled Warfighting. Under the section, “Philosophy of Command”, the Marine Corps has this to say:

First and foremost, in order to generate the tempo of operations we desire and to best cope with the uncertainty, disorder, and fluidity of combat, command must be decentralized. That is, subordinate commanders must make decisions on their own initiative, based on their understanding of their senior’s intent, rather than passing information up the chain of command and waiting for the decision to be passed down. Further, a competent subordinate commander who is at the point of decision will naturally have a better appreciation for the true situation than a senior some distance removed. Individual initiative and responsibility are of paramount importance.

At Whole Foods, decisions ranging from what employees to hire to what products to carry are often made at the team level. The decision-making philosophy at Whole Foods stresses that decisions should be made as close as possible to the place where they will be carried out. And the people who will carry them out should make their decisions without interference from people who are not directly involved. In a world of constant change and short product life cycles, a centrally controlled hierarchy simply cannot see the opportunities or move quickly enough. The use by these organizations of state of the art information technology is not enough because they still lack the processes and the organizational structure to act efficiently and effectively.

Innovative and successful companies will learn to differentiate themselves and find profits in better serving the unique needs of specific groups of customers that they decide to do business with. They will deliver value by employing real-time processes and organizational structures that are already being demonstrated by organizations such as the U.S. Marines and Whole Foods.