The notion of process is of utmost value to organizations, but the reality has often fallen short. The power of process is potentially far more powerful than today’s fragmented practices. With the right approach, however, process can have even more impact on organizational results than it did in the eighties and nineties. More specifically, process is the key to designing and operating organizations to deliver unique, sustained value.

So what is happening today? Sit yourself in the back of the room where the members of a process improvement team are reviewing their analysis of a particular business process before they engage in redesigning the process for better performance. The team is applying a standardized process improvement project (PIP) methodology, so during the analysis phase they created a list of “disconnects” (i.e., problems or deficiencies) they found while examining the current “is” process. They then prioritized the disconnects based on their relative impact on the selected critical business issue, and they are going to use the prioritized list as a basis for questioning the completeness and effectiveness of their process redesign ideas.

But we notice that as the team reviews its disconnect list, every now and then the process improvement consultant leading the team through this exercise will cross a disconnect off the list and add it to another list, labeled “Issues”, being kept on a flipchart sheet on an adjacent wall. Occasionally she reminds the team, “Remember, the Issues List are those problems that may be affecting the process but are outside the scope of our project. So we will report these issues to the Steering Team, but we won’t be trying to address them in our process redesign.”

Well, okay, we understand the improvement team has a defined mission and the process they are addressing has definite boundaries so it makes sense that they narrow their efforts to improving those things that fall within their assigned scope. But as we sit there, we become alarmed as we notice the Issues List keeps getting longer, and it contains what one would presume to be some awfully important things: poorly-designed corporate policies that are making customers mad and employees incapable of serving them effectively; an acute lack of resources in areas most critical to performance; information technology so complicated or hard to use that it makes the process harder for both employees and customers; a missing or bewildering corporate strategy not linked to organizational activities. But we’re not going to be dealing with any of these issues – they are “out of scope.”

Now, the truth is that when we process consultants conducted PIP’s in the eighties and nineties, we often did try to push open the boundaries of projects so that we could deal, whenever possible with most of the problems affecting the process even when they were not strictly within the project scope nor directly related to the process in question. Sometimes we were successful in expanding the scope, but often we were fighting an uphill battle. Once the project had been kicked off and was following a prescribed schedule, everyone involved tended to be loathe to delaying the payoff. And quite often the members of the improvement team were not the right people to deal with some of these big issues that had to do with the management system, with corporate practices, and the like.

So the very things that tend to ensure success with a given PIP-a well-defined scope, clear process boundaries, an improvement team that knows the process well – can also end up limiting the results of the effort. Certainly there are usually significant process improvements to be gained – cycle times cut drastically, processing costs dropping, far fewer product defects, more satisfied customers. But for that process only. And truth be told, unless this process is the very heart of a company -that is, this single process is the chief means of delivering value to the market, as it very well could be in a small company -this is a tactical victory. And usually not a lasting victory. Because as requirements in the external world change, that process can become deficient again.

The greater – and potentially more lasting gains – from process improvement may be at a larger scale. In a seminal article1 in the Harvard Business Review a decade ago, Michael Porter defined effective strategy as designing an organization’s “activities” to be so carefully interwoven, so interdependent, so systemically designed, that they collectively yield competitive advantage. The resulting organization design tends to be so hard to imitate that it sometimes confers lasting a sustained long-term marketplace leadership position for a company clever enough to keep the design intact. Processes being collections of activities that produce outputs along a value chain, Porter is talking about the relationship between process and strategy without ever using the term “process”. In other words, how processes are designed can really make a decisive (that is, strategic) difference not at the single process level but at the level of multiple processes – at the processing system level, the value creation system level, the enterprise/business model level. Now we are talking about the design of process architecture: design of multiple levels of interlocking processes, which is a decidedly different challenge from the one facing the design team for a single business process.

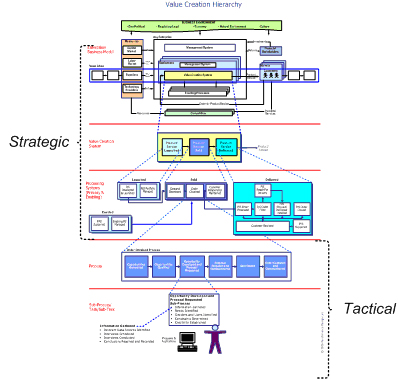

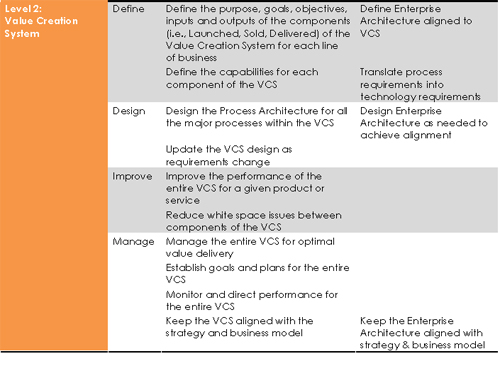

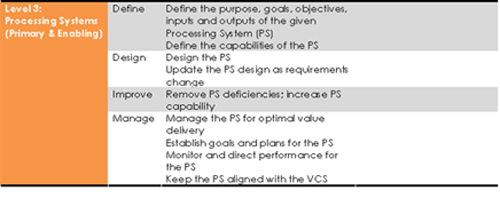

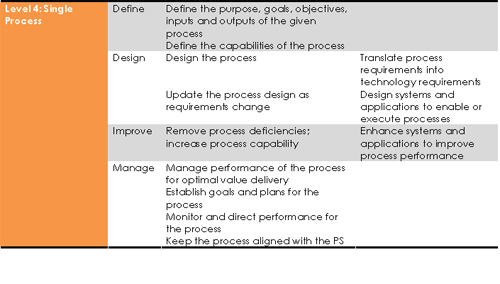

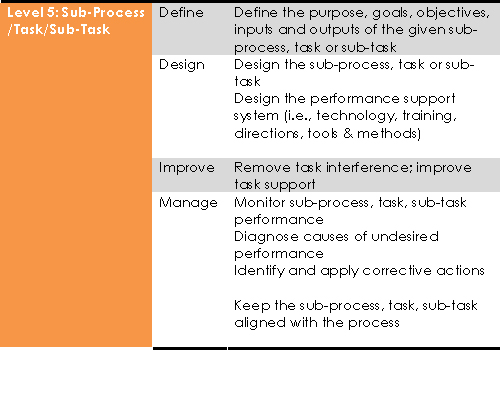

So we have come to believe there are two categories of process design and improvement work, and corresponding scopes, approaches and outcomes for each approach. The two categories of process work are tactical and strategic. Both can be directly associated with the Value Creation Hierarchy (VCH) of an organization. As Figure 1 below shows, strategic process work (i.e., defining, designing, improving, managing) addresses the three upper levels of the VCH – the enterprise/business model (Level 1), the value creation system (Level 2), and the processing systems (Level 3). Tactical process work addresses processes at the single end-to-end process level (Level 4) on the VCH down to the sub-process/task/performer level (Level 5).

Figure 1: Strategic vs. Tactical Process Work

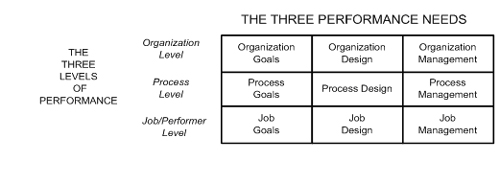

For process practitioners, it is critical for them to understand what category of process work they are undertaking, whether it is appropriate for a given objective, and what they can expect (and therefore promise) to gain as an outcome. For business leaders, it is equally important that they know what category of process work they may be requesting, or commissioning some group to execute, what their own role ought to be for each category, and what they can expect to gain for the organization. This amounts to something of an updating of the 9-cell model in Improving Performance which recommended that to achieve sustained high organizational performance, managers need to address performance in all the following dimensions:

Figure 2: The 9 Variables of Performance

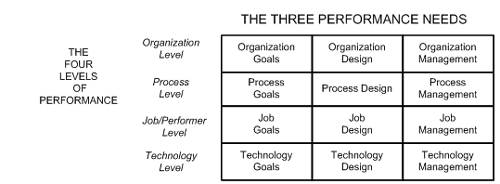

Today we must modify this model to recognize the importance of information technology in the performance equation:

Figure 3: The 12 Variables of Performance

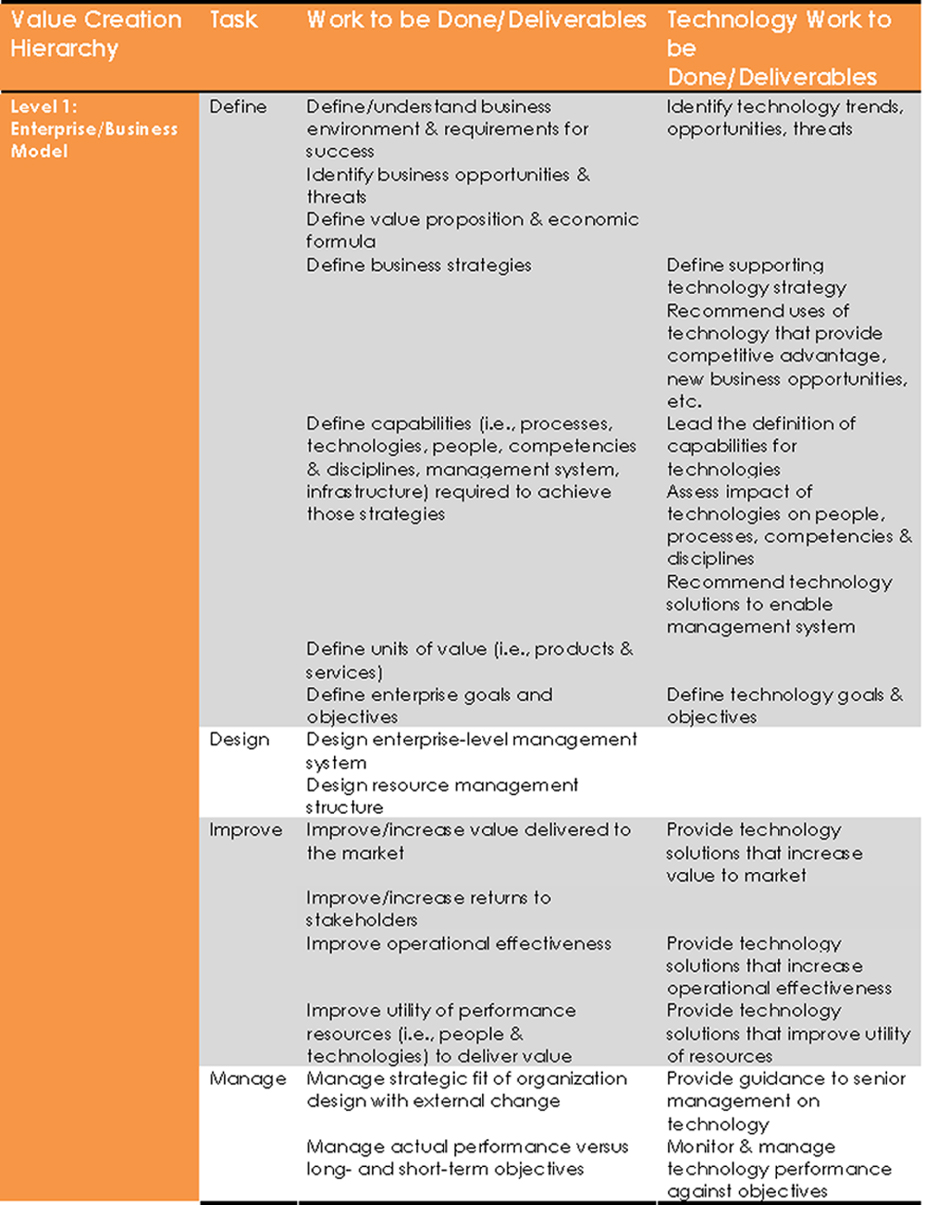

Using the VCH, which embodies multiple levels of process, we can differentiate between the kinds of work and deliverables required at each level of the VCH:

Table 1: Levels of Work

Level 1: Enterprise/Business Model

Level 2: Value Creation System

Level 3: Processing Systems (Primary & Enabling)

Level 4: Single Process

Level 5 : Sub-Process/Task/Sub-Task

From this list of tasks it should be clear that the work to be done at the top three levels of the VCH is strategic, far-reaching and large-scale, while the work required at individual process level and below is tactical, and must be based on the requirements of the upper three levels. The critical leverage for changing performance and competitiveness of an organization is not at the individual process level, much less at the sub-process or task level, yet that is where much contemporary process and technology design continues to be focused.

Moving Up from Tactical to Strategic

Your experience and organizational role may be to focus on single processes, or it may be too early for you to aspire to working higher on the VCH in your particular situation. There certainly is a legitimate contribution to make at the single process level. However, you may be convinced by now that the real opportunity to make a difference is higher up on the VCH – to focus on design and management of primary processing systems, the value creation system, or even the business model level.

1 Porter, Michael, “What is Strategy?”, Harvard Business Review, Nov.-Dec. 1996.