Business Architecture approaches and methods are improving, becoming more formal and standardized as evidenced by the Business Architecture Working Group (BAWG)(1) under the auspices of the Object Management Group (OMG). As with any developing approach or method, a variety of ideas, techniques, terms, expressions and definitions, some old and some new, will emerge. This is most assuredly true for the Business Architecture (BA), as well! This white paper references some of the basic tenets and terms illustrating the convergence of BA thinking from diverse practitioners, business units, enterprises, industries and global regions. The reader is encouraged to look upon this convergence in a most positive manner.

Perhaps an overview of the three key BA tenets that have emerged is necessary. These tenets or generally accepted beliefs and principles evolved from a variety of early BA initiatives; some that were successful and others that were maybe a little disappointing. However, that is how “pioneering efforts,” “prototyping,” and “pilot” type projects contribute to developing successful approaches and methods.

The first and most obvious tenet is that the BA is an “architecture” of enterprise components, not a juxtaposed or classified list of interesting things collected from the enterprise ecosystem. The BA is a structure or blueprint, not a concept, idea, discipline or behavior. Sometimes the term architecture is misunderstood or misused by those not familiar with the fundamentals of architectural and design principles. This misuse is not malicious, but most likely just innocently applied “too casually” by those working in the periphery of architectural endeavors. In a book titled The Object Advantage, by Ivar Jocabson, the author refers to architectures as static structures, with one element linked to other elements to form, collectively, a structure(2). Even though one reviewing a BA model can visualize the dynamics of the architecture and enterprise, it is still a static model illustrating relationships, links and connections in a formal structure.

For several years now, many have observed and realized that the typical alignment of business functions, positioned in various organizational units encourages isolated thinking, sometimes characterized as a stovepipe or a vertical silo. A much broader enterprise wide view is needed; one that is cross-functional in nature, beyond the artificial boundaries of an enterprise function, organization or manager. This expanded enterprise wide view is most certainly inclusive of the enterprise’s functions and organizations, but it has additional dimensions.

This cross-functional insight of the enterprise spawned additional examination of enterprise operations, rapidly expanding the typically accepted views of the enterprise. Some, metaphorically speaking, referred to this rapid expansion as an enterprise “big bang.” Championed by numerous Business Process Management (BPM)(3) initiatives, the other dimensions were exposed resulting in the analysis and significant improvement of the cross-functional, end-to-end activities with a “customer centric focus,” thus becoming the second tenet of BA. The results delivered to and value received by customers suddenly became more paramount than what was going on inside the functions that when integrated, collectively delivered value. Some even considered the variety of enterprise’s activities containing its “people, processes, technologies and security” as encapsulated in black boxes, far more concerned with what the activity produced that is of value to the customer, rather than its internal workings.

This expanded view of the enterprise has four dimensions. In the first dimension are the functions; in the second dimension are the cross-functional activities of the enterprise; in the third dimension are the customers, suppliers, partners and regulators found in the external enterprise environment; and in the fourth dimension are time to market considerations for beating the completion. This four dimensional scope serves the enterprise very well in the 21st Century and has led to a new organizing principle or schema for the BA; that of a customer centric focus! With roots clearly found in BPM, significant improvements in enterprise performance have resulted from seeking out best practices coupled with continuous improvement initiatives. The positive impact and results of these BPM initiatives are truly significant.

As successful BPM initiatives completed and others followed, some enterprises began to realize relationships between them were also coming into focus. Not only were there performance improvements within the individual BPM initiatives, but linking or integrating one BPM with another, delivered additional results, efficiencies and synergy. This “BPM integration” actually became an early representation of the Business Architecture and the third tenet.

For example, a “build to order manufacturer” could collectively, integrate its order fulfillment, its manufacturing/distribution and its procurement BPM initiatives. The premise of this integration is that the purchasing of raw materials is specifically for those items necessary to support manufacturing based on “actual” sales orders from customers in a “just in time” manner; rather than building up inventory levels of raw materials based on “estimated” sales. Improving relationships with suppliers and partners are critical in this example, as well as opportunities for outsourcing. Properly integrated and managed in all four business dimensions, the enterprise will achieve timely fulfillment of customer orders and better customer service while lowering raw material inventory costs, perhaps leading to a competitive position in the marketplace. Considering these kinds of results, some now believe a second enterprise “big bang” lies ahead with the Business Architecture thus again achieving expectations of significantly improving enterprise performance and customer satisfaction.

As the Business Architecture matures, a variety of approaches and methods will evolve just as occurred with Enterprise Architecture (EA) development; for example the Zachman Framework, The Open Group Architecture Framework (TOGAF) and the Department of Defense Architecture Framework (DoDAF). Considering historical examples like this one perhaps it is necessary to understand some of the emerging techniques, terms, definitions and phrases that make up the BA in the context of each tenet.

The first BA tenet is architecture:

An IEEE 1471 website under Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)(4) defines architecture as “The fundamental organization of a system, embodied in its components, their relationships to each other and the environment, and the principles governing its design and evolution.” (Just scroll down to the “So, what is an architecture?” question.) The Open Group Architecture Framework (TOGAF)(5) web site defines architecture as “The structure of components, their inter-relationships, and the principles and guidelines governing their design and evolution over time.” (Just click on “Definitions” on the left side of the TOGAF web page, and scroll down to the second definition under architecture.)

As one can see, slightly different words and phrases, but taken in context, very similar and both definitions are appropriate and acceptable. Any developing architecture such as the “Business Architecture” must clearly imply the formal definition of architecture just provided, inheriting its purpose and intent. This was also true years ago during the development of the Data Architecture, for example. The BA is a structure or blueprint with both internal and external relationships. It is an integrated component within the enterprise ecosystem, not an isolated one.

As long as a BA method’s definition and application of architecture closely resemble the above and is applied in this context, convergent thinking is achieved. Compromising the definition of architecture undermines this tenet, puts the BA initiative at risk and limits expected results from the BA approach or method.

The second BA tenet is a customer centric focus:

This tenet is the implementation and manifestation of the first tenet; architecture. The purposeful integration of cross-functional, end-to-end activities focused on the customer is the first sign of an emerging enterprise structure; an early awareness of the enterprise blueprint. Some may postulate that the organization chart or the typical business/function process model is an architectural model, but that is an “innocent misuse of architecture.” Those models while important to the enterprise and useful for other things are mere classifications of functional elements, but not architectures. An architectural representation of the business/function process model is certainly possible, but that is not how most are designed.

Some assume that the functions, processes and activities found in the classified columns of the organization chart or business/function process model are fully integrated within the vertical silo or stovepipe. A hierarchy built from the classifications of functions, places each process in a column based on sharing some similar characteristic. For example, in the Financial column, one typically finds Accounts Receivable, Accounts Payable, General Ledger, and etc. Attempting to integrate these within the Financial column, expanding up from mere classifications to an architectural representation using functions as the organizing principle will find many connections, but some unconnected components, as well! To resolve the unconnected components, one has to search for relationships within the other enterprise vertical columns and within the extended enterprise environment in order to integrate all of the components. This search for connectivity will eventually lead to resolving all connections, but the result is the creation of a functional view, an internally focused enterprise structure concealing the operational whole. One could take a laptop computer; classify all of its elementary components into columns sharing some similar characteristic. For example, a column for electrical components such as resistors, capacitors and inductors, and a column for fasteners such as screws, plastic clips and hinges. However, one cannot perceive an operational whole from this representation, no matter how cleverly organized; a purposeful organizing principle for the laptop is required in order to realize the operational whole! The same holds true for the internally focused enterprise structure described above. This functional view or internal focus obscures the reason why the enterprise exists, which is to create profit by serving its customers, not its functions.

Enterprises must continually envision new customer product and service opportunities, and on occasion research customer problems. With an internally focused enterprise structure, this is frequently difficult, cumbersome and sometimes even chaotic. The enterprise is not about chaos; it is about connectivity, and causality, and understanding those relationships to both internal and external factors. This connectivity, causality, and understanding are found in an architecture of the business with a customer centric focus, a unifying structure which enables the execution of the strategy through its initiatives to achieve predictable results. Instead of struggling in this chaotic environment, the enterprise needs to boldly stand on the threshold of a new era of structure and order, and take the steps to embrace a customer centric focus.

The unifying structure requires an organizing principle or schema; a purposeful reason for integrating and for the BA, that is a focus on the customers of the enterprise. Developing a customer centric enterprise is most likely the goal of every C-level executive and business unit leader. Practically every corporate annual report states strategic goals and objectives focused specifically on customers; however, the purported enterprise blueprint seldom formally aligns with the customer!

The enterprise must remain steadfast in regard to the second tenet; that of integrating the cross-functional, end-to-end activities focusing on the customer. The customer becomes the new organizing principle for the enterprise, far surpassing the simple classification of functions. It is extremely difficult and impracticable to integrate components without a well defined and purposeful organizing principle. The focus on the customer provides the reason, purpose and criteria for integrating the functional components. Ignoring this precept or rule of action severely impedes integration and leads down a road to nowhere. It reminds one of a delightful quote from Alice in Wonderland(6), “If you don’t know where you are going, any road will take you there.” For the Business Architecture it is clear; the road leads to integrating the cross-functional, end-to-end activities focusing on the customer.

George Stalk, Philip Evans and Lawrence E. Shulman in a “Harvard Business Review” article from March-April 1992 titled, “Competing on Capabilities: The New Rules of Corporate Strategy(7),” used the term capability and argued that corporations are successful because they have an end-to-end capability that enables them to perform better than their competition. Senior managers should see their business in terms of one or more strategic capabilities. The authors state that competitive success depends on transforming a company’s key processes into strategic capabilities that consistently provide superior value to the customer. A capability is strategic only when it begins and ends with the customer.

In James Martin’s 1995 book, The Great Transition, the author states that a capability is a value stream – an end-to-end set of activities that delivers results to a customer. A strategic capability is a value stream critical to competing, performed at a level of excellence difficult for competing companies to copy. The value stream has a clear goal: to satisfy or to delight the customer(8).

Ulrich Homann in a February 2006 article titled “A Business-Oriented Foundation for Service Orientation(9)” defines a business capability as a particular ability or capacity that a business may possess or exchange to achieve a specific purpose or outcome. A capability describes what the business does (outcomes and service levels) that creates value for customers.

Capability is a familiar term in Six Sigma(10) where it states the capability of a product, process, practicing person or organization is the ability to perform its specified purpose based on tested, qualified or historical performance, to achieve measurable results that satisfy established requirements or specifications.

The above references support the concept of cross-functional, end-to-end activities creating value for customers, improving enterprise performance and beating the competition. One can use the term capability, value stream or business capability in this context and easily communicate similar ideas. These references which span seventeen years and different authors are just a few easily found searching the web.

BPM and comparable initiatives employ a variety of techniques for conducting analysis and process improvement. It has several mature, well defined approaches and methods coupled with numerous supporting tools and suites of software. Other disciplines such as Lean Manufacturing(11) and Six Sigma(12) have matured as well. Both Lean Manufacturing and Six Sigma employ the use of value streams and both use a term called value stream mapping.

Lean Manufacturing defines value steam mapping(13) as a Lean planning tool used to visualize the value stream of a process, department or organization (Just scroll to the bottom of the cited web page). Above this definition is the one for value stream which states that by locating the value creating processes next to one another and by processing one unit at a time, work flows smoothly from one step to another and finally to the customer. This chain of value-creating processes is called a value stream. A value stream is simply all the things done to create value for the customer.

Six Sigma states a value stream(14) is all the steps (both value added and non-value added) in a process that the customer is willing to pay for in order to bring a product or service through the main flows essential to producing that product or service. In a Six Sigma definition for value stream mapping(15), it contrasts its approach and that of Lean’s.

Martin in The Great Transition devotes a whole chapter to “Mapping the Value Streams” and in the following two chapters describes the “Outrageous Goals” it can achieve and the “Customer-Delight Factors” to identify(16). Homann says business capability mapping is the definition and clear structural outline of the capabilities and their connections that drive the activities of a typical company.

The above references describe various approaches for analyzing cross functional, end-to-end business processes for significant improvements with a customer centric focus. There are certainly some different words and phrases used to describe value stream mapping and business capability mapping, and depending on the approach, different tools and techniques are used. However, their similarities are clearly evident! Either each matured on its own into a convergence of thinking or the approaches borrowed and shared concepts and ideas from one another, evolving into very similar but unique approaches.

The third BA tenet is BPM integration:

Considering this tenet, integrating BPM initiatives, value streams and/or capabilities in a Business Architecture are most assuredly possible, however, it must stay resolute in regard to the second tenet; that of focusing on the customer and in the context of an architecture, the first tenet. The result of this enterprise wide integration of BPM initiatives, value streams and/or capabilities is the Business Architecture model itself. While emphasis is placed on more strategic value streams and capabilities, all are integrated in the BA.

Stalk, Evans and Shulman state companies create these capabilities by making strategic investments in a support infrastructure that links together and transcends traditional strategic business units and functions.

Martin severely critiques the traditional vertical organizations of most enterprises, wanting to totally redesign them through value stream reinvention. Martin also states that every corporation can be represented as a set of value streams(17). Value streams are frequently identified and determined from the initial, core BPM initiatives, and the other remaining enterprise value streams require identification and integration as well.

A brief discussion of this BPM integration is described by the author of this white paper in an article titled, “Integrating Business Processes in a Business Architecture(18).” The author further defines the integration of value streams as an Enterprise Business Architecture (EBA)(19), explaining the approach for the development of a formal but pragmatic architecture of the business in a book titled, Enterprise Business Architecture: The Formal Link between Strategy and Results.

Homann states business capabilities are the building blocks of the business architecture, so thinking of capabilities as an architectural blueprint is a good analogy; implying a Business Capability Architecture. Homann further proposes modeling the business as a structured—as opposed to a physically integrated—network of capabilities.

Most assuredly, adaptability and flexibility are demanded in any architecture as well as enterprise wide integration. Martin in The Great Transition states, “The term reengineering may be inappropriate applied to business processes because the processes were never “engineered” in the first place(20); and a poorly designed architecture can severely compromise adaptability and flexibility as Homann notes.

The question to answer is, “Does a business structured as a network of capabilities (from Homann’s perspective) complement or conflict with an enterprise engineering discipline (from Martin’s perspective)?” Are adaptability and flexibility better achieved from a truly engineered enterprise using a physically integrated architecture or from a structured network of capabilities? From the perspective of a convergence of ideas and techniques, one could propose using both and that is an excellent answer, too! Some enterprises will prefer the BA modeled as physically integrated while others will prefer a networked approach, and several will like both! Perhaps the best approach to consider depends on the enterprise’s culture, leadership, strategy and the dynamics of its marketplace.

Conclusion:

Given the information provided in this white paper, then how does one define the Business Architecture? First, consider the history of the Data Architecture, for example. Various approaches and methodologies provided very different, but similar definitions and modeling notations for the Data Architecture. The same will occur for the Business Architecture as well! The BAWG defines the Business Architecture as a blueprint of the enterprise that provides a common understanding of the organization and is used to align strategic objectives and tactical demands(21). TOGAF defines the Business Architecture as the business strategy, governance, organization, and key business processes information, as well as the interaction between these concepts(22). (Just click on “Definitions” on the left side of the TOGAF web page, and scroll down to the definition for Business Architecture.) The author of this white paper states the Enterprise Business Architecture defines the enterprise value streams and their relationships to all external entities, other enterprise value streams, and the events that trigger instantiation; it is a definition of what the enterprise must produce to satisfy its customers, compete in a market, deal with its suppliers, sustain operations, and care for its employees(23). The text of these definitions are obviously very different, however, each contains similar points of view using words like blueprint, interaction and relationships in a related context. Each definition must be taken in the perspective of its corresponding approach and practice, and each must inherit the intent and purpose of the IEEE and/or TOGAF definitions of architecture.

A fully defined, articulated and proven Business Architecture approach will not fall from the sky with guarantees for excellent results and outcomes; however, it will evolve over time just as Enterprise Architecture frameworks and BPM approaches have matured over time! The BA has always existed, but its state was unknown or its representation possibly so fractured as unrecognizable. Today, this is no longer true; the formalities of the BA are coming to the enterprise and the enterprise’s competitors as well. The question to ask is “Does executive leadership want to bring the extended enterprise environment to within its sphere of economic influence?” If the answer to this question is “yes,” then a BA initiative makes sense. The answer “no” is also acceptable; however, the enterprise must then hope that its competition is saying “no,” too!

While BA approaches, methods and service offerings are maturing each will use different ideas, techniques, terms, expressions and definitions, however most likely each will incorporate the same basic three tenets previously described. Perhaps the reader has already seen the terms value streams and capabilities; value steam mapping and capabilities mapping; and Enterprise Business Architecture and Business Capability Architecture used in similar contexts. While maybe a bit confusing, BA evolution resembles, for example, the evolution of Enterprise Architecture frameworks and methods.

The enterprise must actively participate in this BA evolution, sharing ideas and experiences all the while communicating in a collaborative fashion, open to convergent thinking from other practitioners, business units, enterprises, industries and global regions. BA expressions need not be so rigid as to impede collaboration, but open to sharing different points of view and seeking to understand similar terms, definitions and phrases. This attitude of collaborating and sharing through BA conferences(24), workshops, focus groups, webinars and the BAWG will bring maturity to a new and emerging Business Architecture approach.

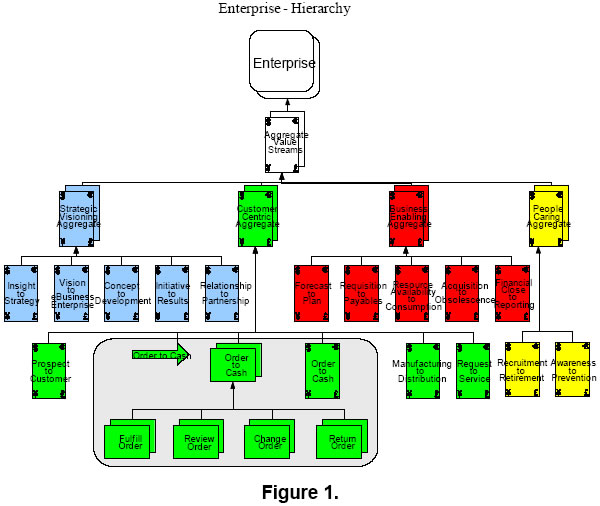

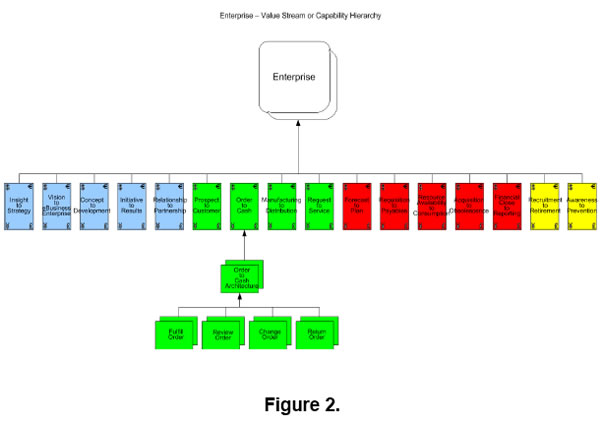

So given all of this BA convergence of thinking, what does an actual BA model look like? Perhaps it is time for the reader to spend some time reviewing an actual BA model; one built on the three tenets just discussed. The model presented in Figure 1 is a representative set of value streams as described by James Martin, modeled as an Enterprise Business Architecture. However, one might possibly use the expression, a representative set of capabilities as described by Homann, modeled in a Business Capability Architecture as seen in Figure 2. The models are best viewed in Internet Explorer 6 or 7 as the hyperlinks are configured for this browser.

Both models are architectural ones of value streams or capabilities, not a grouping or classification of various enterprise elements. All models are connected and integrated with one another through their inputs and outputs. All the reader need do is visit the web site and click on the multi-colored rectangles to expose the detail associated with all value streams or capabilities. Then, once inside a particular model, the reader may again click on the other multi-colored rectangles to understand the integration with other value streams or capabilities. The section with Order to Cash provides a little more detail for analysis illustrating the focus on the customer. As the reader will observe, the models are connected and integrated with one another in a Business Architecture, designed with a focus on the customer or consumer, representing the integration of all enterprise BPM initiatives; a manifestation of the three tenets.

In reality, describing these three tenets with different words, terms and phrases is a naturally occurring behavior, present in just about every commercial and governmental entity. For example, using the definitions provided in this article for value stream and capability interchangeably is not unusual. The same holds true for value stream mapping and capability mapping. Other terms will emerge and preferences selected as BA approaches and methods mature, but with an open minded attitude, convergent thinking will result, and this is a good thing for everyone!

Does the reader agree with the convergence of thinking on BA approaches and methods? Yes; No; Maybe! In any case, the reader is encouraged to research the ideas and information presented in this white paper and to make their own decision.

|

Enterprise – Entity/Enterprise – Hierarchy

|

Enterprise -Value Stream or Capability Hierarchy

EPILOGUE:

Some may disagree with the three tenets presented, the various terms reviewed and the convergent thinking described in this white paper. Therefore, some additional references are provided for consideration.

Architecture was initially defined in ancient times by the Greeks, Romans and Egyptians, and it resides in all engineering disciplines as illustrated by the definition in the IEEE standards. Some non-technically oriented people may cringe at engineering terms like architecture, desperately clinging to functions; however this behavior sometimes masks resistance to change or unwillingness to conformity and standards. Architectural principles are practical, learnable and present in many aspects of daily life. An architecture is a structure; and this definition and understanding is ubiquitous. For addition info on this tenet, consider the article “Defining the term: Business Architecture(25).”

Ask any CEO about the importance of the enterprise’s customers (or clients, or guests or passengers, etc.). A customer centric enterprise is paramount to success. The CEO may laud some enterprise organizations, some regions or divisions and even some key leaders; however, it is the results and outcomes delivered to customers from the enterprise’s cross-functional, end-to-end activities that achieve success for the enterprise. Focusing on isolated internal functional activities is so last century! In the 21st century it is clearly the customer!

For additional info on this tenet, consider the article ”Customer Centric Behavior and the Business Architecture(26).”

Enterprise wide integration and its intricacy may bother some because of its complexity. Shifting the paradigm from function to cross-function was tough enough, but ratcheting it up another notch and seeking a competitive advantage by integrating one core cross-functional, end-to-end set of activities with a focus on the customer with another one, and then with another one, and then with still another one, is downright mind-boggling. Here again, think about what the CEO wants; an enterprise full of isolated functional thinkers or a cadre of visionaries who articulate the enterprise as a fully integrated ecosystem working in harmony focused on the profit generating source, the customer. For addition info on this tenet, consider the article “The Business Architecture, Value Streams and Value Chains(27)”.

References

1. Business Architecture Working Group.

2. Ivar Jocabson, Maria Ericsson and Agneta Jacobson The Object Advantage: Business Process Reengineering with Object Technology (ACM Press 1995), page 97.

3. PCMAG.com/encyclopedia definition of Business Process Management (BPM).

4. IEEE 1471 website, Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ), “So, what is an architecture?

5. The Open Group Architecture Framework (TOGAF) “Definitions” on architecture.

6. About.com: Quotations.

7. George Stalk, Philip Evans and Lawrence E. Shulman, “Harvard Business Review” March-April 1992, “Competing on Capabilities: The New Rules of Corporate Strategy.

8. James Martin, The Great Transition: Using the Seven Disciplines of Enterprise Engineering to Align People, Technology, and Strategy (American Management Association 1995), pages 305 and 104.

9. Ulrich Homann, MSDN Architecture Center, “A Business-Oriented Foundation for Service Orientation.”

10. iSixSigma Dictionary: Capability.

11. Lean Manufacturing Concepts.

12. SixSigma.org.

13. Lean Manufacturing Resource Guide, Lean Glossary, Value Stream Mapping and Value Stream.

14. iSixSigma Dictionary: Value Stream.

15. iSixSigma Dictionary: Value Stream Mapping.

16. James Martin, The Great Transition: Using the Seven Disciplines of Enterprise Engineering to Align People, Technology, and Strategy (American Management Association 1995), Chapters 8, 9 and 10.

17. James Martin, The Great Transition: Using the Seven Disciplines of Enterprise Engineering to Align People, Technology, and Strategy (American Management Association 1995), page 124.

18. BPMInstitute.org, Articles, “Integrating Business Processes in a Business Architecture.”

19. Ralph Whittle and Conrad B. Mryick, Enterprise Business Architecture: The Formal Link between Strategy and Results (CRC Press 2004), page 31.

20. James Martin, The Great Transition: Using the Seven Disciplines of Enterprise Engineering to Align People, Technology, and Strategy (American Management Association 1995), page 104.

21. Business Architecture Working Group.

22. The Open Group Architecture Framework (TOGAF).

23. Ralph Whittle and Conrad B. Mryick, Enterprise Business Architecture: The Formal Link between Strategy and Results (CRC Press 2004), page 31.

24. BusinessArchitecture.org, Welcome.

25. Ralph Whittle, BPMInstitute.org, Articles, „Defining the term “Business Architecture”?

26. Ralph Whittle, BPMInstitute.org, Articles, “Customer Centric Behavior and the Business Architecture.”

27. Ralph Whittle, BPMInstitute.org, Articles, “The Business Architecture, Value Streams and Value Chains.”