So, you’ve read all the right books on lean, agile, and process improvement. You’ve drunk enough of the “quality” cool aid to believe that if everyone else “got it” things in your department or firm would be so much better; you can actually imagine how things could be faster, better and cheaper. If only others could see, taste and implement that same vision.

You follow this excitement up with spending your scarce resources on training sessions for some of your managers, setting up a book club so others can be immersed without the travel and training expense, and you’re even considering hiring a consultant to come in and help coach you and your teams. The pain of your last improvement initiative, however, hangs in the culture like a bad suit – all wrinkled and inappropriate for today’s needs. Time is running out and there are people above you and/or outside your firm wanting results.

If you fall into this category and/or if you are simply looking for ways to improve your team interaction and the results from those interactions, there are some tried and reasonably “true” approaches for you to consider. All of them are easy to apply, but they will take your intent, patience and your involvement. Without those three ingredients, nothing will change but with them in place almost anything is possible – just beware, the results may take you places you never thought of going.

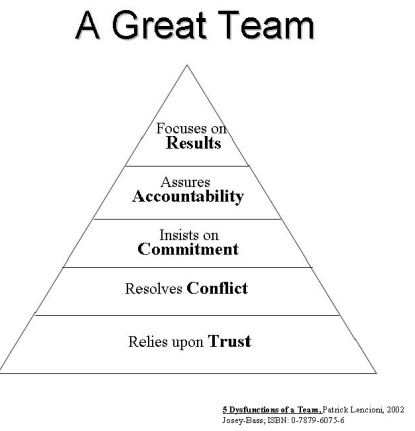

So, where do we begin? My first recommendation to clients is to buy Patrick Lencioni’s book entitled Five Dysfunctions of a Team and if appropriate have all your managers read it as well. In my mind, this is one of the best management books ever written and it’s an easy read (written in a business fable format). The basic premise is that Kathryn, the new CEO, must focus her executive team on improving results before the firm loses significant market share. All of the departments are fighting against each other to assure none of them is seen as the reason for the firm’s demise instead of working together to resolve the major issues.

![]()

The keys to their success include focusing on the greatest business opportunities first, developing an agreeable plan of work within the executive team, establishing a commitment between each other to meet those objectives, and in so doing establish a culture of conflict resolution and trust that will sustain them through the tough times to come.

The most important ingredient for me is the fact that Kathryn knew what she needed from the team and worked with each of them individually and as a group to bring out those collaborative and productive behaviors (see the article entitled “Discovering and Hiring Collaborative Leaders”). In addition, when individuals did not live up to the expectations she had for the role they filled, she helped them find new positions within the firm and/or other ways for those individuals to leave. Bottomline: Kathryn knew she wanted her team to define and stay focused on the most important business issues, work as a team to resolve them, and trust each other in the process of meeting those demands. She was patient up to a point and then, when it became obvious that something or someone wasn’t working well, she made the appropriate changes. In the process she also learned more about herself as a leader and what she could do better the next time.

The lessons I focus on to help teams become more like the one Kathryn developed include the following five development objectives.

- Go slow to go fast; focus on business value

- Expect your team to cooperate and work together

- Facilitate conversations with purpose and inquiry

- Define what trust means in your group

- Provide and receive feedback

Business Value

The first objective may not sit well with those of you desperate to get results from a failing system, but there is no way, and I repeat, there is no way to change human behavior quickly unless we are in a situation where there actually are no alternatives (e.g., situations that threaten your mortality; WARNING: if you chose to threaten people, you’ll get away with that only once before you suffer a rebellion). So, if you want a group of people to change their behaviors and become more cooperative and collaborative you’ll need to find their motivations to do so, focus on the outcomes you and they want to create, and keep the faith through the learning process. In organizational development parlance, this is what consultants mean by “going slow to go fast.” You will need to set the ground work, establish the team’s purpose, assure they buy-in to the results and are willing to make the needed changes in process, roles, and even personal behavior before you will see the results you really want.

In this initiating period, you may have team members read books, discuss the implications, and/or send some folks to training on being better collaborative leaders. The hard work, however comes when you get your team together to define and focus on the most important business issues, develop a plan of work to improve how they reach those outcomes, and then setting up ongoing work sessions to hold each other accountable. While much of this requires a focus on transforming the organization, the principles can be applied at any level where teams of people gather to accomplish work. You must begin with a purpose, a sense of the business value being created, the working agreements each team member lives by, and an ongoing way to assure people are living up to that purpose.

Cooperation

The second objective, “expect your team to work together” is one you must hold initially and expect others to inculcate as time passes. For reasons too lengthy to go into in this article, most leaders have established their success by out-competing other functional areas within the firm instead of working together to improve process flow, reduce waste, and deliver practical results that please and exceed customer expectations. Similarly, team leaders, in many cases believe their teams are the enemy, a group that needs to be controlled, and the reason why they may not be successful – “if only those people would work together, we might get something done.” If either of these occur to you, please look in the mirror and know that it’s up to you to expect the team to work together, even if you are in a matrix organization. Your job is to establish the environment in which people feel comfortable working together, take pleasure in accomplishing new challenges, and share information freely about what’s working and what needs to be improved. Without your interest in their success, a battle will always ensue over who’s in control and the outcomes will always be less than preferable.

When you go into your next management/leadership meeting listen for language that indicates people are working together. If they are, you’ll hear your operations or productions person saying something like “Sally, I know you’ve got a marketing initiative coming up soon, could we talk about the production details so I can assure we’re ready for the delivery date?” In addition, you’ll begin hearing conflict or disagreement as a good thing if it’s aimed at a common goal. For example, you might hear your financial officer saying “George, I heartily disagree with implementing your idea now because, while I think it’s got a lot of merit, I think we need to focus on the other things on our plate if we’re going to reach our business goals this quarter.” In both these cases, you will need to be patient as long as you can to let the team resolve their own issues whenever possible.

Purpose & Inquiry

The third objective in building a collaborative team focuses on the ability to design and facilitate conversations with purpose and inquiry. While this may seem intuitive, it is far from a normal practice in the world of work and discourse. I often say that if I could do one thing to change how business is conducted I’d post a note on all conference rooms or anywhere people are gathered for a meeting that says “If the meeting you are about to attend has no stated purpose please return to something that does.” As a guerrilla tactic, I’ve actually posted signs that said that without the permission of the firm and just sat back to watch what happened.

The point is to spend just a few minutes of your time at least on defining the purpose of why you’re gathering people together and how the session will be conducted. To that end, I think you should minimally do two other things to assure your meetings are productive: 1) create an agenda using questions; and 2) define how decisions are going to be made during the session. The question format forces you to be sure the meeting really needs to be held (e.g., if you already know the answer, why hold a meeting – just write a memo and let people go on with their work). And determining how decisions will be made begs other issues like whether you need a formal facilitator, the types of information needed prior to a decision being made, and who gets to actually make the decision. You’ll be surprised that answering these questions at the beginning of a meeting and/or before particularly meaty topics actually speeds up the process of making decisions and thereby shortening those hellish meetings where nothing seems to get done and everyone leaves with a different understanding of what needs to be done.

Trust

The fourth objective of defining what trust means in your group builds on and utilizes the practices developed in the first three. Quite a few people have said to me, and I agree, it’s inappropriate to trust everything about me in the work place. So, what does it mean to rely on trust when I’m not sure I actually do trust people? In fact, for most people, trust means becoming so vulnerable that they can’t imagine ever offering any level of trust – which only exacerbates the ability to speak openly, resolve conflict and work as a team.

And, it wasn’t until I was working with a team interested in building a stronger sense of trust but found themselves locked in a functionally matrixed organization that I actually discovered a good rule of thumb for trust in the work environment. In this case the organization fed off people’s competition and supported functional differences more than it built reasons for collaboration. Fortunately, they were all being pressured by outside forces to improve their productivity and that pressure gave them the impetus to at least sit down with a third party facilitator and discuss what trust and cooperation actually meant to them. After almost two days of exercises to draw out what people needed from each other and defining working agreements that everyone could support we were almost ready to conclude and go play a round of golf. It all seemed almost too easy – a text book case of how to run and enjoy a team building session, when I asked how people felt going out of the meeting (tee time was 30 minutes away).

And then the bomb dropped.

The second to last person to express their feelings about the two day offsite experience looked at one of his colleagues and said: “I’m really not impressed with any of this stuff because at the end of the day I really don’t trust you to do what you say.” As I stood there in shock and dismay, the person to whom this comment had been made jumped in and said something so profound I use it to this day to help teams define what trust really means in a work context. She responded “look, I get it that we don’t have proof that any of these working agreements will make a difference, but what I can promise you is that if I say I have your back on a decision that’s exactly what I mean and I will do everything in my power to assure you are successful. However, if in the meeting or during a decision making session, I tell you that I can’t support something you’re proposing, and you go out and do that thing anyway I will definitely work against you on that endeavor.” She continued: “do you trust that I will consistently act in that way and is that sufficient for us to continue to find ways to better work together?”

After a bit of conversation around that solution both parties agreed that at least that was an honest way to approach trust building and that it was sufficient to move forward. And, in fact those two intentionally paired in the round of golf and further discussed what that agreement meant to them and have found many more ways to collaborate since. The challenge is to speak your “truth” and find ways to move the conversation forward in a way that you feel is appropriate and meaningful without giving up who you are in the process.

Feedback

The final objective of providing and receiving feedback seems to be the one we least practice and when we do least well. Kathryn tried several times to give her Marketing Director feedback about her behavior but in the end had to resort to releasing her from her duties because she refused to hear what was being said. In addition, Kathryn was constantly gaining informal feedback from her team about what was working well and what she needed to do differently.

The improvement I’d make to Lencioni’s fable is to be more intentional about giving and receiving feedback in a timely fashion. In order to that though you need to have established the business purpose, expectations for people to work well as a team, and a trusting environment in which people can more easily resolve conflicts for feedback to be most effective. But once you have created that type of environment feedback becomes just another learning device used to make improvements in personal behavior, team dynamics and productivity. The best approach I know for giving and receiving feedback is to:

- assure the purpose for the conversation is well stated (e.g., the purpose of this assessment is to help us run a better advertising campaign next time)

- ask or state what worked well since the last time you did an assessment; focus on actual examples of what people did well; e.g., describe how people showed up to work early and left later without being asked instead of “people really worked hard.”

- Ask or state what might be improved in the next period of time. As in discussing what worked well, you’ll need to use specific examples so the person/team understands what you actually mean. For example, instead of saying “we need to be more creative” say something like “as we begin a new project I’d like to see us using some form of group brainstorming and story boarding to draw out our creativity.”

- Establish an agreement on what you will try differently in the next iteration of time to make improvements and set a date/time to review how those ideas worked for you.

This process of reflection, retrospective or assessment is so foreign to most of us that we leave it out of our lives. The reality, however, is that without this practice no improvement process will ever deliver ongoing enhancements and is probably destined for the dust bin of other failed initiatives.

Summary

The key to building teams in collaborative work processes actually has more to do with how we are as human beings than it does with the specific methodological expectations. And, as we peel back the layers of that onion we find that a group’s focus on a common goal, their ability to trust each other sufficiently to move forward, and the leader’s ability to be intentional, patient, and involved will define how well an improvement process will be accepted and implemented.